UNEQUAL

Brewing Event

An Evening of Drinking With the Ancients

March 6th, 2025

Words by Megan Suka

“Nearly 4000 years ago, in what is now the land of Iraq, a song was composed in honor of the divine Ninkasi, goddess of a golden, delicious, nutritious drink that we love and enjoy to this day.”

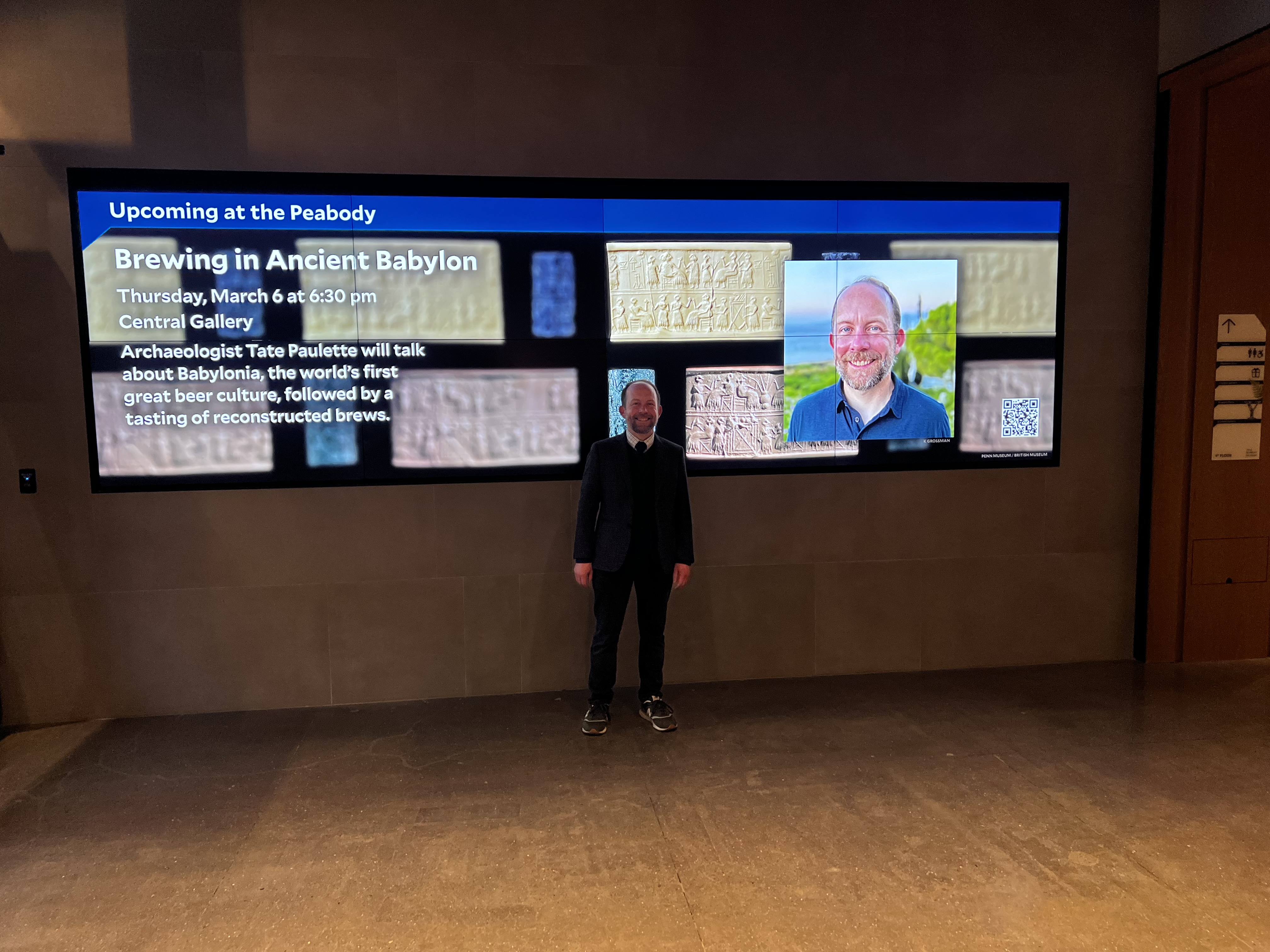

With this preface, co-instructor of NELC120 Unequal, Gojko Barjamovic of Yale’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, introduced Dr.Tate Paulette of North Carolina State University to a full house of 160 guests in the elegantly adorned Great Hall of the Yale Peabody Museum. Here, Paulette delivered a lively guest lecture based on his 2024 book In the Land of Ninkasi: A History of Beer in Ancient Mesopotamia. Paulette’s book is the first text to pull together the evidence on ancient brewing in a monograph form. As the world’s foremost expert on ancient beer brewing techniques and what he calls “gastro-politics,” Paulette deftly wove archaeological evidence, ancient texts, and the formidable task of their interpretation into a story-driven account of Mesopotamian brewing practices.

“What we have in 3000 B.C. Mesopotamia is evidence of the world’s first great beer culture,” Paulette told the audience. Research in recent decades, particularly in the arena of trace residue analysis, has given us a fragmentary knowledge of brewing practices in earlier cultures. What’s remarkable about Paulette’s work in third-millennium BC Mesopotamia, by contrast, is that “We suddenly have a wealth of evidence to work with ... This is the first time we can really see a beer culture in its full complexity.” This picture, he says, comes to us in the forms of archaeological, artistic, and written evidence.

One of the more amusing pieces of archaeological evidence Paulette shared with the audience was a cylinder seal (an ornately-decorated object which, when rolled over wet clay, left an imprint of an image unique to its owner—akin to a signature) that seemed to leave little room for misinterpretation: its imprint shows a man drinking beer through a straw, simultaneously laid out over a woman, in what one hopes was a passionate, drunken love affair. “In some ways,” Paulette noted with a grin, “drinking culture hasn’t changed a bit since ancient times.”

Etiquette aside, Mesopotamian drinking culture was as socially significant as it was economically indispensable. Thousands of cuneiform tablets have been recovered which detail administrative accounts of commercial logistics, like grain stores, delivery receipts, brewing recipes, and tavern locations. They were remarkably specific: you might find an inventory of types and quantities of beer and instructions for how much should be delivered to various locations. Other evidence includes protective rituals; prayers and hymns to Ninkasi, goddess of brewing; drinking songs; and narrative accounts of drunkenness varying from “slightly buzzed” to what can only be described as “dangerously wasted.”

After the lecture and a lively Q&A, guests eagerly swarmed the bar set up among the towering dinosaurs in Burke Hall for a chance to sample ancient brews. As an accompaniment to Dr. Paulette’s talk, Yale School of Medicine researchers Vanessa Todorow, Zane Johnson and Christian Mahl—who have spent the semester as auxiliary course instructors in NELC120 in charge of the brewing team—offered samples of two Mesopotamian beers that they brewed specially for this event, following recipes developed in an inter-departmental effort to re-create these ancient beverages.

Rather than brave the line for the food tables snaking outside the banquet hall, I decided to wait it out and eavesdrop on a group of people while waiting for a chance to ask Dr. Paulette further questions. By the time I did reach the bar, the charcuterie tables had been reduced to piles of wilted lettuce and grape stems—signs of an evening well-enjoyed by the many guests in attendance—but I was lucky that neither of the two kegs I’d hoped to sample had run dry. The first beer, simply called “sweet beer,” had a low alcohol content with what Todorow called “a bready profile, with some fruity and mildly sour notes.” The other, named the “good beer,” had a stronger, 5-6% ABV content, with a more acidic, citrusy profile, accompanied by herbal and peppery undertones.

As both an accessible educational experience open to the New Haven public and a hands-on enrichment of the brewing team’s course contributions, the event was a fascinating, fun, and charming experience for all in attendance. Learning about Dr. Paulette’s research, while simultaneously incorporating his insights with the process of our archaeological and brewing efforts in class, brought us closer to understanding the significance of Mesopotamian beer culture than we could have achieved in the classroom alone.

The lecture and event was generously organized with funding from the Yale Peabody Museum, Yale’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Department of Anthropology, the Yale Ancient Pharmacology Program, The Yale Babylonian Collection, and the Franke Program in Science and the Humanities.