UNEQUAL

The Museum Group

Exploring curation of ancient objects at the Yale Peabody Museum.

Getting Started

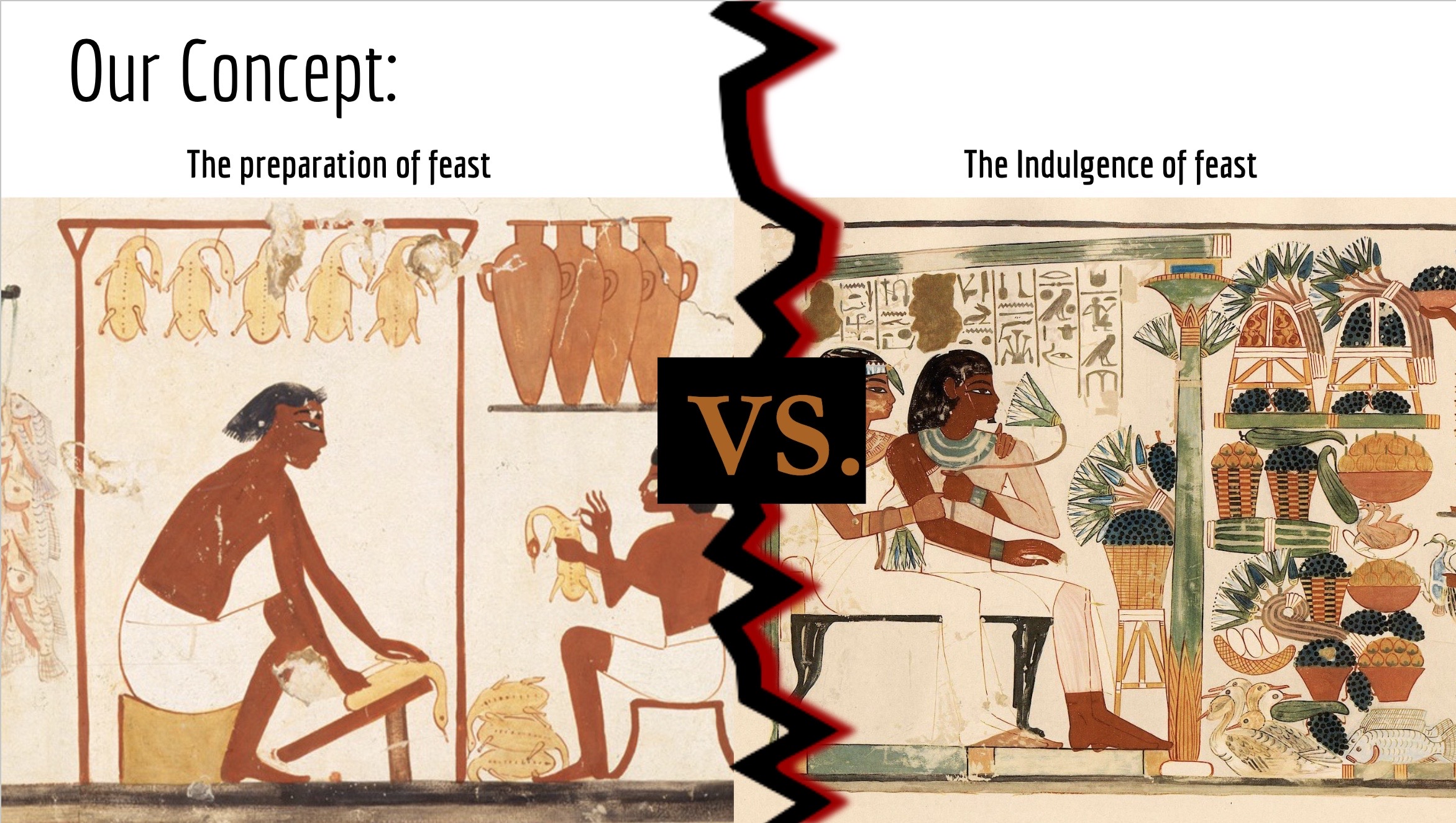

The students of the museum group had the opportunity to curate a museum exhibit at the Yale Peabody Museum. In order to do so, the students first had to learn about curation and what objects would be possible based on the space provided. Through working with the Peabody curators, they learned the size restraints of the case as well as the limitations caused by security. The space they were given is near the lobby and gift shop which unfortunately meant the case did not have the security that some objects would require. After learning more about the process, it was time for the group to pick their theme. They discussed many ideas and ultimately decided to do two separate but connected themes for the cases. In one case they would focus on the preparation of the feast and in the other, the indulgence of the feast. This theme truly captured the essence of the course Unequal. Throughout the semester students have read ancient recipes, recreated meals, and learned about the history behind the food/drink and how it was enjoyed. After picking this theme, it was time to go through objects and plan out the case.

Breaking Down The Curatorial Process

1. Picking A Theme

As we drafted our exhibition themes, it became clear that even in brainstorming, these concepts had to be grounded in material culture. Thus, we immediately began selecting objects from the collections to help visualize potential themes. It was immediately evident that some stories of inequality were easier to tell through the collections than others. We realized that the narrative of our cases had to be succinct while still allowing us to represent multiple object types, scales, and regions. Thus, a sort of “let them eat cake” theme arose. By exploring inequality through food and drink, we are able to work with objects related to daily life, funerary culture, and elitism.

2. Choosing Objects

Our goal was to select a visually diverse set of objects that illustrate inequality in daily life. For instance, we chose to display two cups: one made of redware and one made of ceramic with ornate designs. We found that the ornate ceramic cup came from a tomb, while the redware cup was discovered buried between two village houses. Though the archeological contexts differ, these objects still demonstrate inequality. Having a proper tomb was typically associated with elite status in Ancient Egypt, this decorative ceramic cup was likely a valuable ceremonial object, not meant for practical use. The redware cup, on the other hand, was functional and common. We believe that displaying objects like these can paint a comprehensive picture of inequality through the culture surrounding food and feast.

3. Adjusting Object Selection

After we felt confident about our object list, we formally requested items through the Peabody. We quickly ran into a few issues, which forced us to replace several objects. The problems were primarily related to the size constraints within the cases, in addition to some conservation concerns. Custom mounts were not possible given our limited time frame, so particularly large, fragile, or non-freestanding objects were automatically eliminated. For instance, a fragmented stela we planned on being the visual anchor in the case was shockingly roughly 140 lbs and thus too heavy to be exhibited. We collaborated with Peabody conservators, curators, liaisons, and many other fantastic people to find replacement objects. We then constructed a more feasible object list that still fit our narrative.

4. Designing The Cases

Once the final item list had been compiled, we began to formalize the layout across the cases. We allocated one case to describe the making of the feast and the other to the feast itself, separating objects accordingly. To better visualize the layouts of each case, various members of our group created various digital models of the space. This included illustrated renditions of the cases in addition to 3-D models accomplished through CAD. We wanted the display to look balanced while still mixing object size, type, and color. After a few drafts and ideas for posters on the top shelves, we shared our designs with the museum team at the Peabody.

5. Coordinating Object Delivery and Preparation

Though many of the objects on our list were conveniently stored at the Peabody, many require additional steps before their exhibition. For example, one culinary tablet is on display, so we had to commission a 3D-printed replica. Another piece, “Fragment of an Offering Table”, was reported to have a “salt problem” and needed cleaning. Other objects, such as a large amphora, are still on pallets at West Campus, further pushing our exhibition date. After accounting for cleaning, transportation, and installation, we expect the exhibit to be complete by the end of June.

6. Drafting a Narrative

Crafting the purpose of our exhibit involved creating a compelling narrative that was both cogent and meaningful. For each case—“Feast Preparation” and “Feasting Itself”—we distilled intricate historical relationships and power dynamics into focused introductory labels that abided by the museum’s 20–25 word “big idea” and 60–65 word supporting text format. We prioritized clarity, emotional engagement, and thematic cohesion. For “Feast Preparation,” we highlighted the labor and power behind every elaborate feast. Our words needed to connect unassuming objects into a unified narrative, enabling visitors to see that ancient feasts were not merely a matter of celebration or nourishment but of power, reinforcing economic and ritual order.

7. Writing Labels

Like much of this process, writing labels for our objects proved a bigger challenge than initially anticipated. We gleaned most information through the LUX catalog, but our labels were made robust by utilizing resources such as transliteration books to help decipher tablets. The biggest challenge was prioritizing information that would appeal to the general public, not just a member of this class. This meant thinking carefully about how much context to give, how to phrase things clearly, and how to make sure each label supported the bigger story we’re trying to tell.